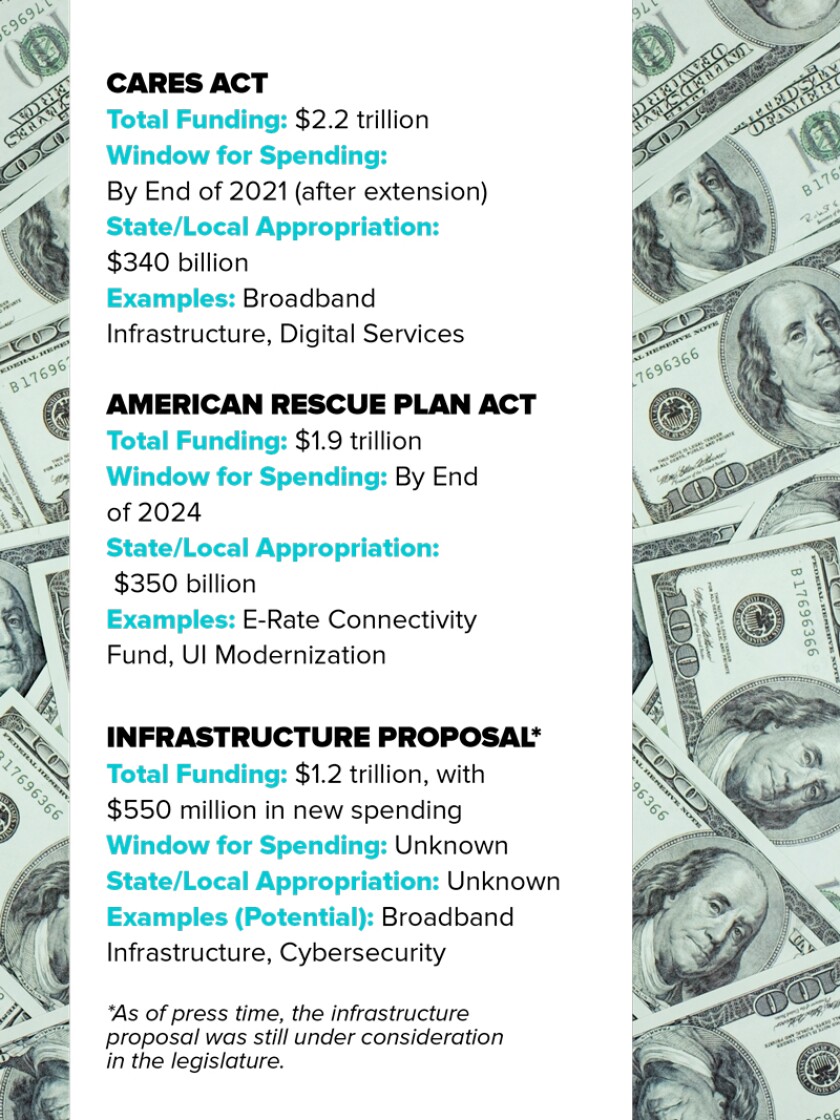

Yet here we are, with a May 7 Pew report indicating that 29 states “had overcome” devastating losses in tax revenue by February 2021. And then there’s the hundreds of billions of dollars that state and local governments will receive from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and other federal support. Across the country, there’s talk of striking while the iron is hot for a number of tech-related government projects, whether they be around broadband, cybersecurity or modernization of decades-old systems.

“It really is an interesting time because states were planning for these cuts and watching very closely — and I think even when things started to recover, we were very conservative in that because nobody wanted to get in a bad situation,” said Shelby Kerns, executive director of the National Association of State Budget Officers. “Feels like a lot of opportunities in many states. Some are still not quite rebounded, but they do have federal aid now.”

You don't just abandon what worked what what helped you survive. You still need to be somewhat hyper-focused in the flush times. Otherwise, when you get to the lean times, you won't be prepared for it.

Great proclamations about economic opportunities create great expectations — and there lies the risk.

“States are going to be under a lot of pressure, because … there’s always more ideas on how to spend money than how to cut money,” Kerns said. “They’ll be under a lot of pressure to evaluate those requests. But it’s always better to focus on things that can be sustainable. And that’s part of the problem:

A lot of those requests and ideas have an ongoing component that people need to be very cautious about … or again, you’ll just end up … making budget cuts.”

“I think flush times are a bit dangerous for government,” said Phil Bertolini, vice president of e.Republic,* and former CIO and deputy county executive of Oakland County, Mich. “You have money coming in from all different directions. You don’t necessarily know what to do with it.”

The danger won’t be the same for everyone. Some states and local areas will face tighter budgets than others. Whether in a lean time or a flush time, how can government IT leaders help foster sustainable organizations?

Wikipedia

HAVE A PLAN AND TELL THE TRUTH

Bertolini knows a thing or two about economic highs and lows. Thinking about his 31 years of serving Oakland County, Bertolini cited multiple years during the Great Recession as the toughest time of his career when it came to budgeting. While the recession impacted the entire country, Michigan, as the focal point of the American auto industry, felt the vice grip before other states.

“We were the center for R&D for all of North America in our county,” Bertolini said. “When the auto industry started diving and bankruptcies and bailouts and so on, we were right in the middle of that, and our tax revenue was dropping dramatically. To this point, my home in Oakland County is still worth less than it was in 2007. Even though the real estate market is booming — houses are staying on the market for a week — my house is still worth less than what I paid to build it in 2004.”

What made Bertolini’s experience so difficult during the recession was an ever-shifting financial target. His team would pinpoint a number that it needed to hit and then act accordingly. Pay cuts were taken. Infrastructure was trimmed. Projects were axed. All of these things and more were done to hit a number. But then the number would change, which meant more sacrifices.

“Every time we thought we had it solved, we’d take another hit in revenue,” Bertolini recounted. “Another tax didn’t come in as it was projected. I equated it to climbing up a hill of mud, where I climbed up a foot and we’d drop two feet, then you’d climb up two feet and drop three feet.”

Having experienced this frustrating cycle, Bertolini shared two essential lessons for any IT leader. First, everyone needs a plan for lean times. The planning should start as early as possible and should account for as many situations as one can foresee.

“Just like disaster recovery, just like a fire, just like a tornado, just like a hurricane, if you don’t have the plan in place ahead of time, you’re going to suffer during, right?” Bertolini explained. “But if you have the plan and all you have to do is open the book and turn the page and actually enact the plan, that’s better. Have a plan for this, too.”

The second lesson relates to the psychological and emotional stress that can plague members of an IT team during hard budget times. The idea is simple in concept, but takes fortitude and integrity to execute day after day: Tell the truth. Don’t hide or dumb down information, and don’t tell people tomorrow will be better if tomorrow really isn’t going to be better. Maintaining trust with staff is a critical part of resilience.

“They know when you’re lying,” Bertolini warned. “They know when you’re sugarcoating, and they will turn on you if they believe you didn’t treat them fairly. It was a very important thing, and I was over-communicative with my team during those tough years.”

Shutterstock

DON'T BE FOOLED BY EXTRA DOLLARS

Evanston, Ill., will receive $43 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds. Luke Stowe, administrative services director and CIO for Evanston, describes this influx of money as a once-in-a-generation occurrence.

On the other hand, he’s not ready to say this historic amount of funds represents a clear flush time for the Chicago suburb of about 75,000 residents.

“It’s very strange,” Stowe said. “It’s both lean and flush. It’s lean because we’re still coming out of COVID, and we’re not where we need to be from a revenues and expenses standpoint. On the other hand, we’ve got this $43 million funding source coming online now, so it is very odd. It’s the best of times and the worst of times.”

Stowe believes due diligence is key to weathering this unusual scenario. From an IT standpoint, anything that gets funded by ARPA either needs to be a one-time investment or something that can be sustained from other sources of money.

“So much of the international conflicts are handled in a digital fashion,” Stowe pointed out. “It basically puts the state and local agencies potentially on the front lines of international conflict. Previously, the city of Evanston didn’t need to worry about China or Russia or North Korea or these other bad actors, but now we do. And obviously, the average community is not necessarily staffed or funded to do that. Thankfully, we’re seeing more and more momentum at the federal level to properly fund the state and local agencies on that front.”

Bertolini suggested IT leaders should be as careful during flush times as they are during lean times. When extra money comes through the door, the natural temptation is to loosen up and kick off new projects. However, if you start a new program, recognize that the program may not go away, even after it’s no longer useful.

Another mistake during a flush time is to abandon standards and processes that would be followed during a lean time. If a proposition involves a lot of cash, think about the principles that would help your organization stay afloat during a more fiscally uncertain year.

“You don’t just abandon what worked and what helped you survive,” Bertolini said. “You still need to be somewhat hyper-focused in the flush times. Otherwise, when you get to the lean times, you won’t be prepared to handle it.”

Stowe mentioned a key point about federal funds: If the feds give states and local areas more time to spend money, there’s less reason to rush with spending. Stowe is thankful Evanston has until the end of 2024 to spend its ARPA dollars.

“As opposed to ‘Here’s a ton of money, and you’ve got 12 months to spend it. Go!,’ I do think that it’s good that we’ve got an extended runway of time to spend the money so that we do it the right way,” Stowe remarked, adding that his city is using some of that time to get maximum feedback from the community about its needs.

David Kidd/Government Technology

THE RESILIENCE OF OPEX AND THE CLOUD

Steve Nichols, Georgia’s chief technology officer since 2002, can identify multiple budget- and resilience-related benefits for his state since it moved toward an opex model about 10 years ago in the wake of the Great Recession. Perhaps the greatest advantage is being able to make changes quickly and efficiently.

“Almost all of the infrastructure, we either roll it up into an as-a-service, or if we hold title to it, we’re leasing it instead of purchasing it, so that gives us a lot of flexibility to ride out those storms, up or down,” Nichols said. “Normally, I would say states that are still in that fully owner-operator model, really the only tool in their toolkit is they can just wait longer on a refresh if they get into a lean year. In our case, we can start to turn things off.”

The opex switch from capex doesn't happen in year one. It's more like year three that you start to see the benefit, because you have the cost of doing it and then you have the cost of riding it longer term.

“If you’re in an agency and you have an application that is a little antiquated … you’re going to see a budget surplus as ‘Now is the time to go ahead and refresh that application,’” he explained. “The way that manifests for us is an agency might come and say, ‘We’re going to rebid application XYZ, and we’re going to need a new environment to run it on.’ Or it might be, ‘We’re going to move off the mainframe.’ This has been happening a lot over the last couple of years … Because we’re in an opex model, we’re just going to source all of that.”

Nichols admitted, however, that the opex model can lead to some “tough conversations” with agencies during lean times. It means central IT can’t give agencies discounts, nor can individual agencies cut costs by avoiding refreshes.

“This stuff is all leased. … Payments are due every month,” Nichols said. “I would say that by making it more flexible for us, we’re pushing that consumption management model down to our customers, and they have to participate in the management. They can’t just say, ‘GTA [Georgia Technology Authority], just don’t bother to refresh anything this year.’”

From a budgeting standpoint, Bertolini also prefers the manageability and predictability of an opex model. He likes that the model reduces the costs of replacements, as companies regularly update cloud applications, meaning that “you’re just paying by the drink.” The challenge is with instituting opex.

“Some governments only budget on an annual basis,” Bertolini said. “The opex switch from capex doesn’t happen in year one. It’s more like year three that you start to see the benefit, because you have the cost of doing it and then you have the cost of riding it longer term.”

Both Nichols and Stowe spoke about how an opex approach can help with workforce, which is tied to budgeting. Nichols pointed out that the acquisition of talent can be a time-consuming process without the helping hand of a big company.

“It’s pretty easy to flex up and get more help if you don’t have quite the right expertise or you just need more bodies or whatever it is,” Nichols said. “Whereas, [under] that owner-operator model, if you’re trying to go with local contractors or something like that, you’re a little more constrained. Maybe it’s going to take longer to actually hire people in if you’re doing it yourself versus calling up your vendor partner.”

Stowe, meanwhile, shared a fear that likely crosses the minds of all public IT leaders: What if you can’t keep the talent you hired to, say, build and maintain a data center?

“Especially if you’re a smaller government agency, it can be really tricky to maintain that talent in-house,” Stowe said. “I would rather use that in-house talent for other things, whether it’s enhancing digital services, or spending more time on cybersecurity, or doing a better job of aligning with our business units … rather than trying to build out a data center, if you will. It makes more sense to outsource more of that. From a disaster recovery or business continuity standpoint, I think you’re probably better off, in most cases, if you’re in the cloud. If there’s a fire at your data center, that’s going to be a huge problem, whereas if you’re mostly cloud service, you’re going to be able to respond better.”

Nichols recommends partnering with multiple companies under the opex model for increased resiliency. Since transitioning to opex, Georgia has gone from relying on two companies to contracting with a more diverse range of businesses for different tech needs.

“If one of them was to have some pivot — they’re getting out of the state and local business or some other business event — we’re not having to rebid the whole world,” Nichols said. “We’re just having to rebid one particular chunk of what we’re doing, where there’s going to be other companies that can service us.”

*e.Republic is Government Technology’s parent company.